The Shot

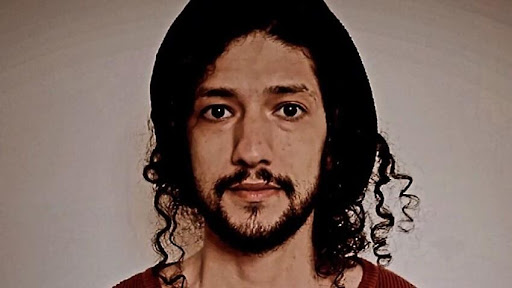

Mehdi Ali: “A sort of illusion”

The Government wants us to believe that there’s no point talking about the plight of Mehdi Ali and the dozens of refugees currently detained without limit in Melbourne’s Park Hotel. Our Federal Parliament wants us to believe that his imprisonment is justified, required and fair. More than 1500 refugees sit hopeless and desperate in a variety of Immigration Prisons around Australia. Some, Like Mehdi Ali, have been incarcerated for nearly a decade or more.

High-rise prisons; plate-glass windows bolted onto single-room apartments, three-star hotel complexes along major roads, places we drive past every day as we chat about the trivial or dwell on the day’s work, beneath cardboard signs held up by the atrophied arms of the invisible. From the age of 15, for over nine years, we have held Ali in stasis, out of sight and mind.

Over this pandemic, throughout the lockdowns, we have experienced a small taste of this stasis. We have felt the depression, seen the developmental challenges in our kids, understood the psychological and societal implications of isolation. Some of us are in the streets protesting, most of us are counting the costs, all of us are aspiring to our own freedoms from this pandemic.

Mehdi has learned to play classical guitar. In this endless detention, he plays European toccatas and fugues, harrowing contemporary renditions of songs like “Tears in heaven”. He has spent his entire adult life in arbitrary detention, yet his grasp of philosophy and his understanding of humanity, beauty and pain are nuanced and humbling.

Many of us went to school with people like Mehdi; many of us are friends with someone like him. He is just like the kids we grew up with around Melbourne’s north in the 1990s, a refugee from oppression, just like the children of refugee families who came to Australia fleeing the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990). These kids became part of our story. We went to school with them, played footy with them; their families established communities with us. They were ducēs, youth leaders, premiership winning footballers, successful business people – they became heavily involved with our local political branches, and the parties recognised them as essential to our story. And to winning elections.

Mehdi Ali could have been one of our schoolmates too, yet by the time Cathy Freeman ran the torch up the Homebush stairs to light the Olympic flame, we were unknowingly poised to descend into a period of moral capitulation that would sweep through every one of us. We shut the gate in 2000 with Howard’s contemptuous lie of children overboard, only we would decide “who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”, and we closed our minds collectively ever after. The war on terror, the Bali Bombing, events woven into the shallow history of our desperate quiet Australia, further hardening us to the genuine pleas for help from Muslim “boat people” because any one of them could be a terrorist.

By the time Mehdi arrived here in 2010, we were deep into a collective humanitarian ossification. He, like all other boat people, was processed under the hard-nosed policy of the previous Labor government and diminished, mollified, and silenced over the next LNP decade of hardening and cruel disinterest. The “trial and error” nature of a bipartisan immigration detention program planted the seeds of his, and thousands of others’, invisible horrors. The offshore solution was clumsily benchmarked, sterilised, commercialised in this period. The government’s opacity was supported by the largest swathes of the press, who in turn helped cultivate this new inhumanitarian paradigm. And we swallowed it gladly.

Over the recent freedom movements, the tradie sit outs, hotel quarantine, the hospital PCR tests, many of us have moved around Mehdi and the refugees at the Park Hotel in Melbourne. When the entire world watched Novak Djokovic arrive at Mehdi’s hotel in political and diplomatic hijinks, we briefly got a reminder of the draconian powers of the Immigration Minister as it applied to the world’s number one tennis player, and a glimpse of how they applied ad infinitum to the people like Mehdi staying next door.

It was hard speaking to Mehdi. Everything he said had a clarity that cut through my train of thought and revealed the ignorance within my questions; a reminder of this man’s willingness to show us all a way out of this fatal moral position and our careless refusal to accept his generous offer.

Mehdi spoke of his position as “continuous constant trauma” where he has been rendered and “treated in a hidden system”. He talks about “time fooling him” as the years of hope and despair turn on their heads randomly and chaotically in an unending nightmare. His words, “A sort of illusion”. Grieving for the epigenetic bonds of community that have been stripped from his essence by a callous political system.

On this issue, both major parties have been supported by the corporate press, responsible for moulding perception and shaping the narrative over two decades, generating a maelstrom of subjective reporting: a Murdoch-Howard software model integrated with neoliberal circuitry.

Meanwhile, the public broadcaster has failed to provide the contrast, to provide a line of sight to help Australians articulate this humanitarian disaster. They have been incapable of delivering the raw facts in a way that illustrates the simple nature of this national shame. When the ABC asks Mehdi why it’s important for journalists to “keep their concerns up” for refugees in hotel detention, when they ask about the “condition of the hotel”, it speaks more alarmingly to an inability for modern journalists to empathise, understand or communicate key issues in the national interest.

We have become a mediocre nation that has lost its ideas, limping through a mining boom and two illegal wars. Add our refugee human rights record and our failure to give First Australians constitutional recognition and we have little to show so far in this millennium. The hardening of our hearts began with children overboard but soon became bi-partisan tough-talking on refugees. Now it appears the powerful in this country read from the same song sheet on many issues, singing in harmony with corporations who have redefined our concept of compassion and community, pulling our gaze into the endless trap of consumerism and empty words, rather than appealing to the goodness of our hearts and the warmth of our outstretched hands.

“By my window is a tree, it’s the darkest picture that I have ever seen”.

Mehdi cannot hold on much longer, for we have broken him. There is no reporting, no angle, no Immigration Minister that can speak of inadequate powers, no perspective or context because both major parties think that there are votes in this strategy. They think this is what we Australians want.

But, is it? Our apathy deepens from decades in which we have offshored our ideas, casualised our philosophy and removed full-time positions around our history of compassion and acceptance. This is the reason nothing changes. Our collective whimpers, our lip-service, and the cyclical nature of our collective denial towards these people is our national shame. We are all guilty of letting our governments assume that this is who we want to be.