The Shot

Ben Roberts-Smith – the beautiful things he’s seen

On the same day Afghan farmer Ali Jan was smashed off a rocky cliff by Ben Roberts-Smith with such force the farmer’s face split open and his teeth exploded out of his face, Australia’s then Defence Minister Stephen Smith was occupied in an ABC studio telling Australians,

“The Australian Defence Force and its personnel have a very highly regarded reputation in the way they deal with these matters … taking very great care to avoid involving civilians in warlike operations.”

It was possibly around this same time on that same day that Ben Roberts-Smith ordered his soldiers to shoot Ali Jan, the handcuffed wounded farmer, dead. By the time the blood from Mr Jan’s gunshot-riddled body and his exploded face ran into an Afghan cornfield in deeper stains than we will ever acknowledge, Stephen Smith was back in Canberra preparing for his next round of interviews with the day’s media and posing for photographs with visiting Singaporean dignitaries.

Eighteen months earlier, when Ben Roberts-Smith moved his 2 metre-high frame to the stage to receive his Victoria Cross in January 2011 in his hometown of Perth, the crowd bulged with the weight of all the very important people present. Such was the number of very important people that day, it took Smith several minutes at his speech’s beginning to acknowledge the assembled throng: Prime Minister Julia Gillard, Governor General Quentin Bryce, Chief of the Defence Force, Angus Houston, Leader of the Opposition, Tony Abbott, everybody basking in the glory of the great hero.

This grand ceremony of Roberts-Smith’s military acclimation had originally been timed to coincide with the opening of the Australian War Memorial’s new VC exhibition in February 2011 – a $4.6 million extension to Australia’s war temple in the heart of Canberra, a memorial that brings in millions of visitors every year. The original AWM ceremony to Roberts-Smith had been organised by the AWM director Brendan Nelson, a deeply devoted and long-term fan of our two-metre high hero who kicked farmers off cliffs in far-away lands and had them shot in the head in cornfields.

After articles began appearing in mainstream media in late 2010 and early 2011 questioning the awarding of the VC to Ben Roberts Smith due to reports about his war time pursuits that included threatening to shoot his fellow soldiers in the back of the head and machine gunning a disabled Afghan civilian, the Defence department suddenly decided to expedite the VC ceremony and brought it forward one month to January 23, 2011.

In fact, for a speedy four year period, from 2009 to 2013 the awarding of Australia’s Victoria Crosses happened with such startling alacrity, the Directorate of Honours and Awards in the Department of Defence must have barely had time to breathe.

Australia has awarded 101 Victoria Crosses in total since 1900, the bulk of these being awarded during the first and second world wars. Prior to the VCs awarded under the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd government from 2009 to 2013, Australia’s last VC had been awarded forty years before in 1969 to Vietnam War veteran, Keith Payne.

It is a little known, and probably trifling fact, that of Australia’s 101 Victoria Crosses awarded over a 123 year period, four of them were approved under the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd government, a government increasingly under pressure to bring an end to a war that had stretched out since 2001 and was becoming ever more unpopular as each year, and each death, unfolded. What is probably an even more trifling fact, is that 3% of our 101 VCs were approved by one man – former Defence Minister Stephen Smith, now working industriously in Australia’s High Commission in London.

None of these trifling details, of course, factored into the decisions made by Justice Besanko in the Federal Court this month when he found substantial truth to the claims by journalists Nick McKenzie, Lyndelle Barnett and Chris Masters, that Ben Roberts-Smith was a murderer, an abuser, a war criminal and a man who bashed unarmed Afghan civilians.

Despite claims to the contrary by Sky News presenters mainlining a war they had never been part of, Besanko’s decisions were laid out with precise, detailed reasonings and justifications. His decisions are made even more grave by the application of the Briginshaw Principle which upholds that higher standards of strict proof are necessary to support judicial findings of very serious allegations. Not that any of that would have helped the family of farmer Ali Jan, but at least his brother-in-law got to testify about what he’d seen and what he knew to be true – that “the big soldier” had kicked Ali Jan while he was handcuffed, ten metres down into a dry creek bed and had him shot.

If it is true that every day spent serving in a war is a day marked off your time in hell, then it must also be true that the shared hell for war crimes must belong to those who perpetrate them and perhaps those who seek to ignore them. But who are those who seek to ignore them? We can never know. While it is difficult to finally pin down a war criminal, it is almost impossible to pin down those who looked the other way. After the Ben Roberts-Smith war crimes verdict, the stage was suddenly empty.

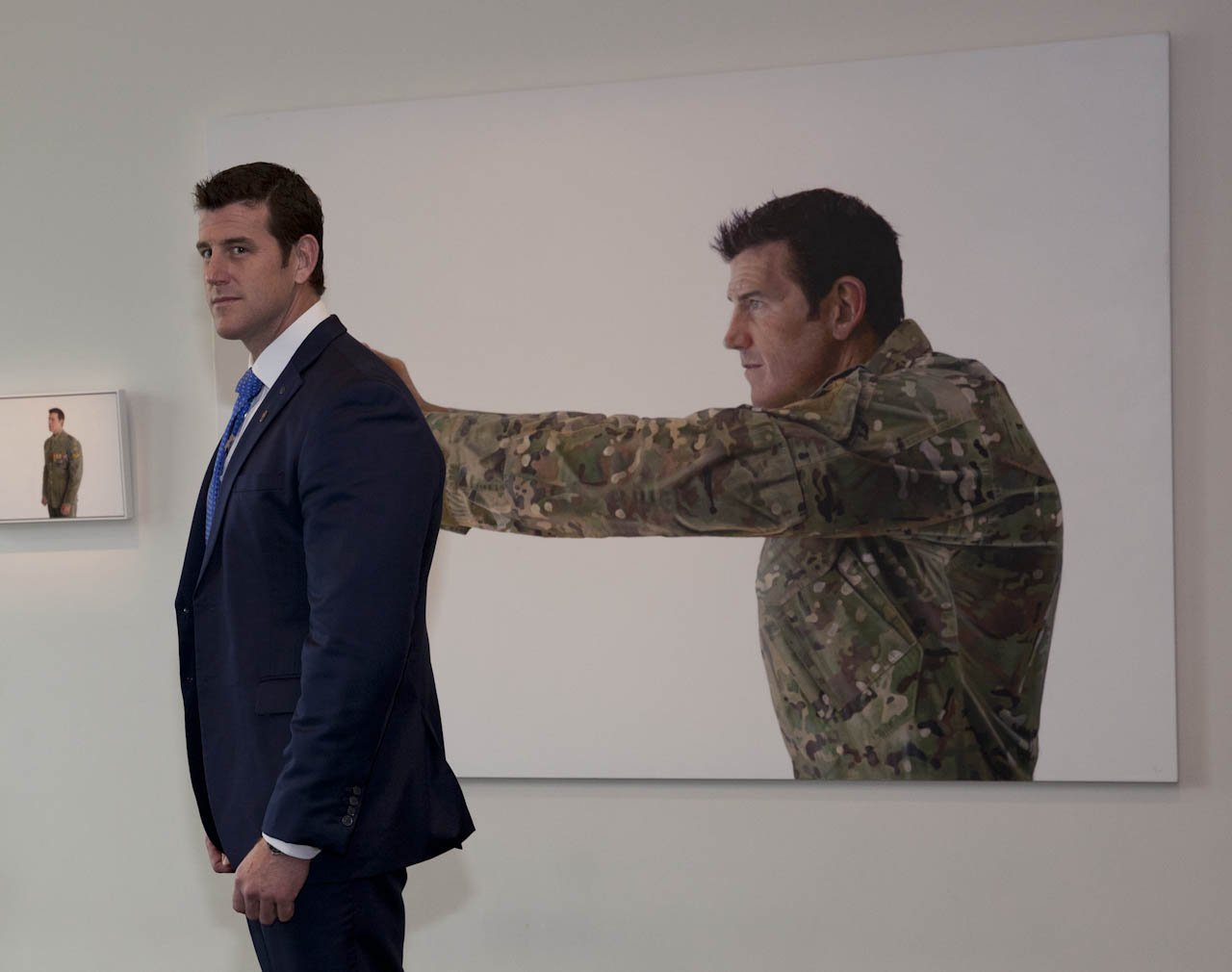

The Australian War Memorial has begun quietly, without any fanfare, removing online pages and references to Ben Roberts-Smith. They still have to grapple with what to do with their altar to Roberts-Smith that they have constructed over many years, which includes a massive painting of his visage across a wall, recordings of his voice and a life size mannequin dressed in his uniform, but strangely no recordings of him telling a fellow SAS soldier he would “put a bullet in the back of his head”.

At least that’s what Person 1 told the court had happened to him, and Justice Besanko found this allegation to be contextually true. Often, in the event of a crime or the retelling of facts, people misremember things. Usually not because they have malicious intent, but because the human memory is fallible and time and place all work, by turns, to make a perpetrator red haired, or blonde haired or perhaps he was wearing a black jacket – who can remember?

But with Roberts-Smith, the polarised versions of events recounted in court were utterly irreconcilable. Take the alleged death of a terrified teenage Afghan boy in Fasil, in November 2012. He was taken prisoner by Australian forces from a vehicle at a checkpoint. “I made him out to be late teens … a bit chubby, and shaking in terror. He appeared extremely nervous and trembling uncontrollably,” Person 16 told the court.

Person 16 handed the teenager and another man over to Ben Roberts-Smith. Around 20 minutes later, a radio call came through that two Afghan “enemies” had been killed just up the road. Person 16 said he crossed paths with Roberts-Smith days after the incident within Australia’s Tarin Kowt defence base and he asked Roberts-Smith: “What happened to that young fella who was shaking like a leaf?”

The court heard Roberts-Smith said: “I shot that cunt in the head … I pulled out my 9mm, shot the cunt in the side of the head, blew his brains out. It was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.” In court, Roberts-Smith denied the incident ever happened.

In the closing scenes of Apocalypse Now, Col. Kurtz writes to his son, “As for the charges against me, I am unconcerned. I am beyond their timid, lying morality. And so I am beyond caring.” Is that why Roberts-Smith embarked upon one final mad, ill-fated mission – his defamation trial? A man unconcerned, a man beyond caring, except perhaps for all the beautiful things he’d seen.

And as a reward for all the beautiful things he’d seen, we gave our hero our country’s highest honour, the Victoria Cross. After all, despite bashing an unarmed Afghan civilian in the face with his fists and the stomach with his knee until the civilian collapsed, despite an Afghan wife weeping beside a cornfield, back in Australia, Roberts-Smith was the hero Australia needed. Because in the dying days of the Afghan invasion, the federal government desperately wanted a hero to serve up to the nation. No, no, they needed a hero to serve us, to hold aloft. The defence minister Stephen Smith dreamed of such a hero, so much so he could not hear the chatter and the whispers and the frontline reports of abuse by his very own hometown boy.

Australia’s war memorial was so desperate for their hero, they turned him into a two-metre high altar so the masses could worship in their theme-park temple of war. All of them needed a hero. They needed a righteous man, a man who looked death in the eye, and when he wanted, could kill the cunts without remorse.

Australia needed something brave and yes even ugly, from such a fetid, unavailing war. Australians demanded a hero, whatever the price.

And for our sins – they gave us one.

More like this

Dave Milner